It’s the first Thursday of the month. Every inch of the house has been cleaned and the children are wearing their best clothes. The evening air breezes through open windows in quiet anticipation. Unusually quiet for this part of the world perhaps on any other day. After dinner, the family and their guests are moving into the salon. As everyone assumes their seat, the grandmother brings out her radio. At 9.30pm, the concert begins. “We’ve rechannelled the Nile stream. What an event!”, sings Umm Kulthum, Kawkab al-Sharq, The Star of the East. “It will be a change of our life. Not just of River Nile. I can delightedly see a bright future. Factories running, plants on infertile land, abundant blessings for all, and a beautiful road to prosperity.” With her voice, Cairo rejoices. Proud to be Egyptian, grateful to witness Al Sitt, The Lady. “A phase has been completed, and others are still on the way,” she continues, every note a tender promise. “We’ll give the best example for generations. With the will of Gamal and this good nation.” Umm Kulthum concludes after four hours, leaving the grandmother in tears. Slowly, the salon emerges from its trance. A clicking sound. “My countrymen, this is your president Gamal Abdel Nasser speaking. We have begun building the High Dam. It will spread fertile greenery over the desert…”

The rise of Umm Kulthum

Umm Kulthum was born in a small village in the countryside of Egypt’s Nile Delta (c.1898-1904). Her father was an Imam who supplemented his income with music performances at religious festivals. The family toured the Delta performing songs in praise of the prophet, and Umm Kulthum was their shining star. Their popularity with the Upper Class led them to move to the capital where Umm Kulthum sang for larger crowds and collaborated with influential composers and poets. Her career took off under the mentorship of the renowned Sheikh Aboulela Mohammed who introduced her to poet Ahmed Rami; with their help, she established her signature sound characterised by romantic poetry of unrequited love and loss, Arabic modal scales (maqamat), and an exceptional contralto vocal range. At her vocal peak, she could sing as low as the 2nd octave and as high as the 8th octave, and had to stand at least one metre away from the microphone. Her virtuosity seduced audiences into euphoric states of tarab (“ecstasy” or “joy”) in which they would cry out to her, turning her concerts into a spiritual exchange. By the 1930s, her musical talent and carefully curated public image had catapulted her to the top of the industry, selling records from Morocco to India.

After her father passed away in 1931, Umm Kulthum began touring the Arab World and embracing new media. She starred in six feature films during Egypt’s golden years of cinema. In 1934, she secured a deal with the national radio station to broadcast a live concert every first Thursday of the month, prompting many Egyptians to buy a radio for what became a national event continuing for 40 years and beyond her death. Although usually remembered for her love songs, Umm Kulthum was a political artist, careful to maintain the image of a modest fallaha, a peasant girl (turned working-class hero), culturally close to the majority of Egyptians. In the 1940s, she started collaborating with composers and writers who dealt with “ordinary people’s” problems through populist songs in colloquial Arabic. In 1947, she starred in the film Fatma, playing a nurse seduced by the brother of a wealthy patient who first married and then rejected her for her social status – perhaps foreshadowing Egypt’s imminent revolution and the side that she would choose.

The rise of Arab nationalism

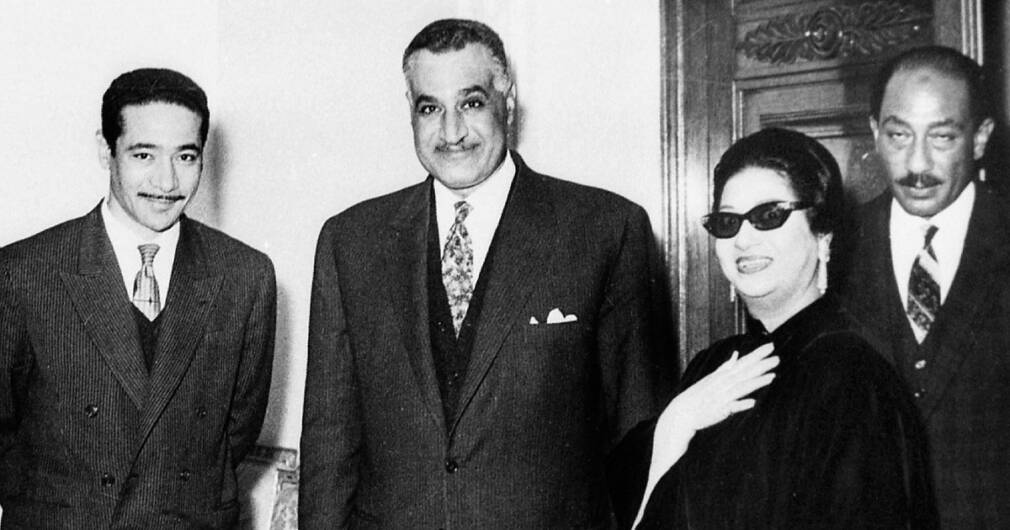

Umm Kulthum used to give private concerts for the Egyptian royal family. But as times changed, she was quick to adapt her music and activism. At that time, Cairo was a bustling, international city, fuelled by visionary politics, anti-imperialist sentiment, and a desire for modernity. Umm Kulthum knew how to tap into these conversations; her music became the soundtrack of this era to which her close friend Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918 – 1970) provided the philosophy: pan-Arab nationalism.

During the first Arab-Israeli War in 1948, she answered a request by an Egyptian legion trapped in Palestine’s Al-Faluja Pocket to sing a particular song. Amongst the soldiers was future president Gamal Abdel Nasser who was establishing himself as the leader of the Free Officers, a group of army generals who wanted a nationalist revolution. Nasser belonged to the first cohort of lower-middle-class cadets who were admitted to the military academy in 1936. He was a charismatic man and a fierce nationalist, determined to transform Egypt into an independent, socialist state free from colonial rule. Upon their return, Umm Kulthum invited the entire army battalion of Al-Faluja to a reception at her home in Cairo, to the displeasure of the royal government and the British.

The July Revolution

In 1952, Nasser’s Free Officers staged a coup d’etat, deposing King Farouk and accelerating the expulsion of the British. Although Nasser was the group’s leader, the nationally respected war hero Mohamed Naguib became its figurehead and Egypt’s first president. Like Umm Kulthum, Nasser came from a rural family of low social status which meant that he had to earn the respect of the Egyptian people. The masses were yet to put their trust into him, and some say that the singer’s public support achieved exactly that. After the revolution, the Egyptian musicians guild banned her songs from the radio, because of her previous affiliations with the royal family. When Nasser heard about this, he is said to have exclaimed: “What are they, crazy? Do they want Egypt to turn against us?”

In those days, hearts and minds were conquered through soundwaves. Nasser insisted the guild take Umm Kulthum back and reinstate her concerts. He began delivering his speeches right after her performances, when the country was tuned in and enchanted. His broadcast show Sawt Al-Arab (The Voice of the Arabs), launched in 1953 on Cairo Radio, became an instant success because it featured her. In the wake of the revolution, Umm Kulthum had adjusted her lyrics and now sang to the working-class (as opposed to her focus on the aristocracy two decades earlier), reflecting the socialist discourses of Nasser’s politics. Mixing music with news and political commentary, Sawt Al-Arab became Nasser’s vehicle across borders, calling on North Africans and West Asians to “break all bonds and shackles and impose themselves on their governments.”

A song frequently played on Sawt Al-Arab was Umm Kulthum’s Mansoura Ya Thawret El Ahrar (Revolution of Freemen, You’re Destined to Victory). “The July Revolution is a powerful one. It inspires its power from its Arabist spirit, from our days, dreams, and from our longing for freedom. We are the Revolution and the revolutionaries. Revolution of freemen, you’re destined to victory. The Revolution is destined to victory and revived by God who offered us ʻAbd al-Nāṣir. With our leader, we shall wipe out our enemy.”

The Free Officers’ gained popularity after introducing a nationwide industrialisation project and far-reaching land reforms that instigated the redistribution of agricultural land from land-owners to farmers. But they also banned all political parties of the old regime, tightened their control over civil society, and put thousands of their opponents in prison. In 1954, Nasser removed Naguib from power and declared himself prime minister. He promulgated a new constitution that made Egypt a socialist Arab state with Islam as its state religion, and received overwhelming approval in the 1956 elections. A few months later, he nationalised the strategic Suez Canal to fund the High Dam in Aswan. This defiant decision against the imperial powers elevated him to become a leader with near-total popular support throughout the region, impressing both his followers and his enemies.

Scoring pan-Arabism

When the UK, France, and Israel invaded Egypt in an effort to stay in control of the Suez Canal, Umm Kulthum gave voice to Egyptian resistance. “Oh glory; oh glory! You were built up here, by our effort and sweat. You shall never turn into humility,” she sang, echoing the speeches of Nasser. Her song Wallāhi Zamān, Yā Silāḥī(It’s Been a Long Time, O Weapon of Mine) was playing on national radio as often as ten times a day. “The nation creeps like light, the people are mountains and seas, a volcano of anger; a boiling one, a quake digging graves.” The crisis eventually ended through intervention by the Eisenhower administration; Egypt, although its military had not stood a chance against the invaders, considered it a success on their part.

Nasser went on to build his pan-Arab dream and created the United Arab Republic with Syria in 1958. Wallāhi Zamān, Yā Silāḥī was adopted as the national anthem of this new country, and remained Egypt’s national anthem until 1971, long after Syria’s recession in 1961. Umm Kulthum was his cultural ambassador, giving voice to the imagination and nostalgia of one Arab homeland. The music, language, and poetry she represented helped construct a narrative of shared identity. At concerts, she wore the traditional clothes of the countries she was performing in, and she used her relationship and experience with the audience to prove that Arab people everywhere are “of one heart and one pulse”.

Umm Kulthum at war

By the 1960s, Umm Kulthum and Gamal Abdel Nasser had become the parents of the Arab World. Umm Kulthum’s music, which had started out as pious Islamic recitation and love poetry, frequently contained messages of violence, mirroring the militarisation of Egypt under Nasser and the idea that belonging meant sacrificing oneself for the nation. Her patriotism reached a peak leading up to the Six Day War in 1967 when she performed “Concerts for Egypt”, fundraising for the army and encouraging the Egyptian population to participate in the war efforts. After the defeat by Israel and Nasser’s consequent resignation, she used her voice to support his return to politics, honouring him with the song Habib el- sha’ab (Love of the people) which was broadcasted almost every day for a month in the Egyptian national radio. It begins: “Stand up and listen from deep down for I am the people. Stay for you are defender of the dam to the wishes of the people. Stay for you are what is left of the future of the people.”

When Nasser died of a heart attack in 1970, Umm Kulthum continued promoting his vision of pan-Arab unity. She has been critiqued for having been a tool used by Nasser. But Virginia Danielson, author of “The Voice of Egypt”, believes that her relationship with the president was mutually beneficial as they agreed on many issues. “They tended to say the same things about themselves, Egypt and the Arab world,” she says. “There are times you don’t know which one is speaking, Nasser or Umm Kulthum.”

Transcending spells

Umm Kulthum died in 1975. Against Islamic norms, her funeral was postponed for two days to accommodate for the four million mourners arriving to bid her goodbye. The only other person honoured with a burial of this scale was Nasser with an estimated five to six million attendees. Their funerals were testament to the intense, personal bonds they had created with the Egyptian and Arab people. Her tarab performances sent listeners into such deeply emotional states and his passionate rhetoric gave hope to such a vast region that it elevated them to become figures who transcended humanity. They invoked a uniquely unifying Egyptianness in a country that is steeped in class difference. While there is much critique of Nasser’s dictatorial rule and perhaps not enough critique of Umm Kulthum legitimising his regime, the pair invented and embodied a form of nationalism, emancipation, and cultural authenticity that struck a chord with millions of people. Together, they built an artistic and socio-political legacy unmatched by any other Arab musician or politician.

“Gamal, example of patriotism, our best Egyptian holiday, is the day when you presided over the Republic. Repeat after me, Our best Egyptian holiday, is the day when you presided over the Republic. Because of your struggle for the rescue of the homeland, your place is in our hearts. A heart defends its love and chooses, and never betrays freemen’s amity. You rid the Nile from all intruders, and it was confused and lacked guidance. You’ve lit a lighthouse in today’s Egypt, and its light spread to other countries. You’ve unified the Arab nation. Repeat after me.”